Precious Spice Metals for High-Tech Products

First Steps

Source: FoodAndPhoto/Shutterstock.com

Strategic metals are usually applied in industry in small doses – as in seasoning in the kitchen. Demand for the rare spice metals is increasing, causing prices to rise in many cases.

Half a teaspoon of scandium for lighter aircraft components, and a pinch of indium for the displays of flat screens and smartphones. Known in metallurgy as spice metals, rare earths and technologie metals play a key role in developing state-of-the-art electrical engineering products. Like the spices in the kitchen that give a dish a distinctive flavor or make it easier to digest, metallic refinements provide or improve special material properties. Often, only small quantities in the range of micrograms and grams are used in production. But despite the low dosage, the metals form an essential component in the material mix of high-tech applications. For example, their absence makes main metals such as iron or aluminum in alloys less hard, corrosion-resistant, conductive or magnetic.

The Salt of Modern Industry

Spice metals are commonly understood as selected technology metals, rare earths and precious metals. They are found in the formulas of many key technologies of modern life: in the production of permanent magnets for e-mobility and wind turbines (neodymium and praseodymium), lasers (erbium, gallium), automotive catalysts (palladium, platinum), photovoltaic elements (indium), computer chips (gallium) and turbine technology (hafnium, rhenium). Like salt in the kitchen, it is impossible to imagine any of these industries without these metals. The development of future technology will also depend decisively on their inclusion. Fuel cells as energy carriers and energy converters for hydrogen depend on adding palladium and terbium.

The Correct Dosage

Similar to using ingredients in the kitchen, spice metals are only added to the production in small quantities. These examples illustrate how low the dosage is:

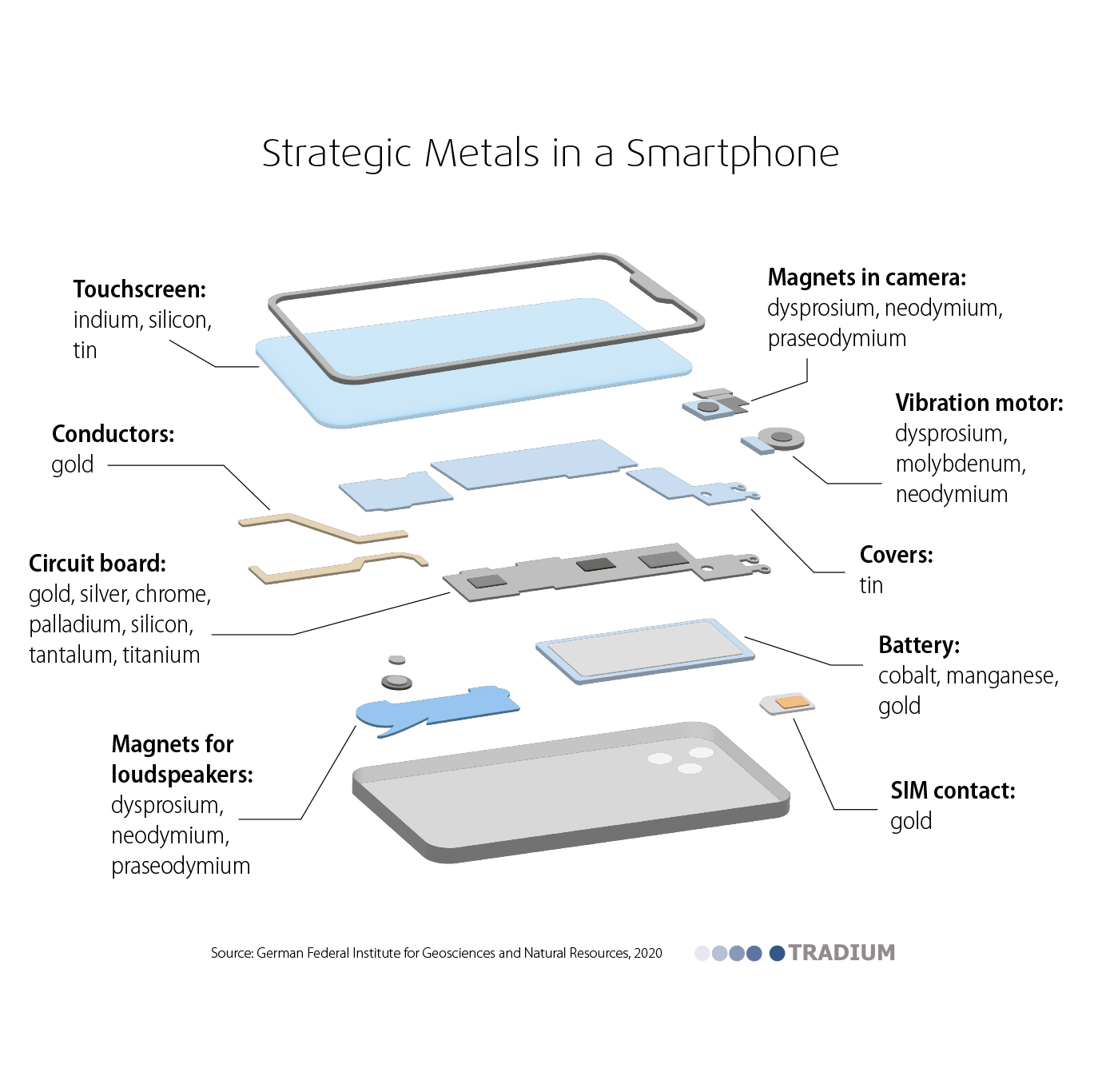

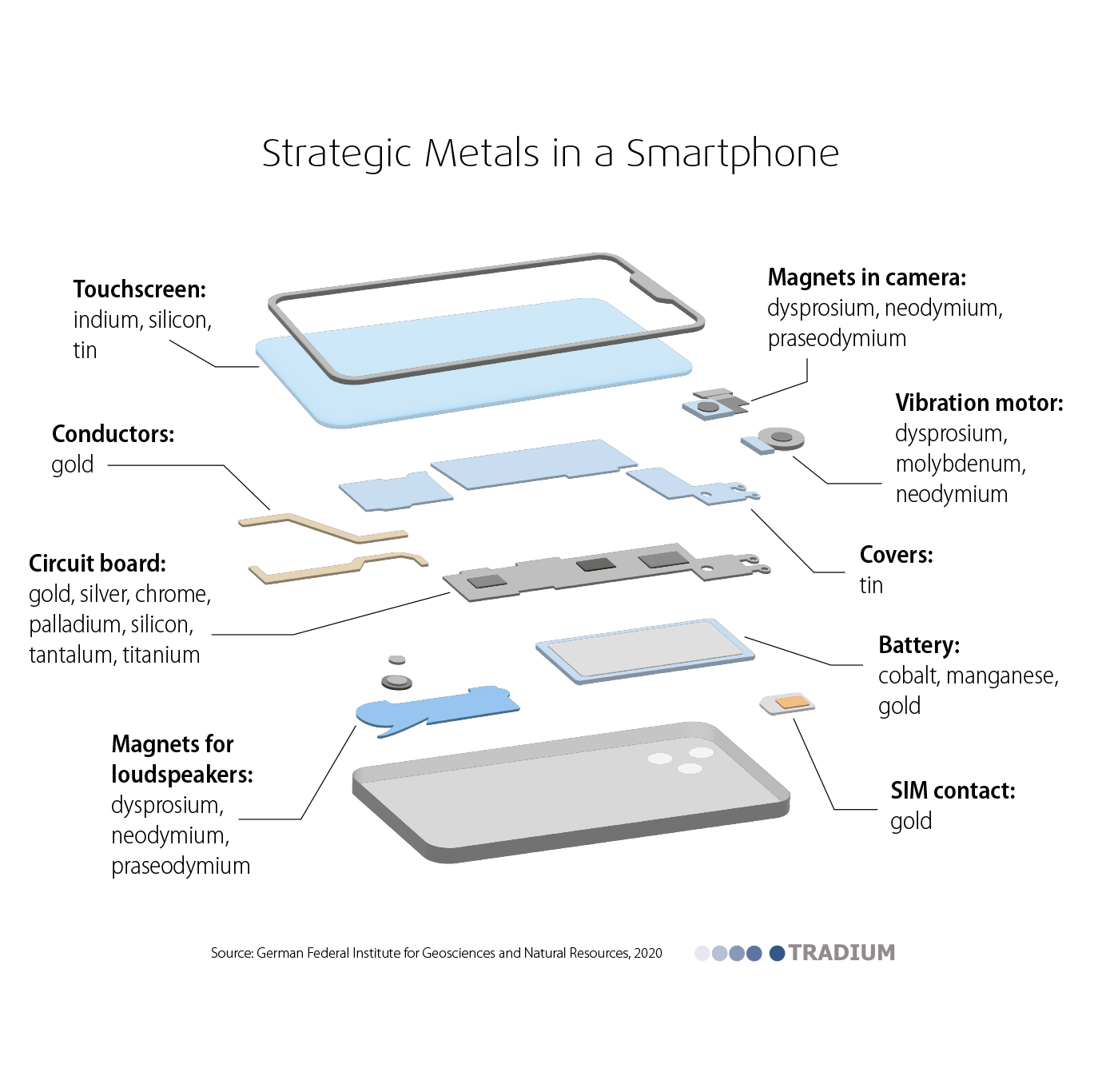

- Smartphone: A 111-gram device contains 0.017 grams of gold, 0.002 grams of palladium, and 0.3 grams of rare earths such as neodymium, dysprosium and gadolinium. In addition, there is indium in equally homeopathic doses: 0.004 grams in the display and 0.0022 grams in the circuit board, as determined by the German Raw Materials Agency and the Federal Institute for Geosciences (in German).

- Exhaust catalysts: With a total weight of about 1 kilogram, each contains up to 7 grams each of platinum and palladium and 1-2 grams of rhodium, the Waste Advantage magazine reports.

- Fighter jet F16: The extent to which rare earths are used in armament technologies is calculated by the news portal rawmaterials.net. The military aircraft, which weighs about 12 tons when empty, contains 420 kilograms of rare earths in the form of cobalt and samarium, among others.

Even if rare metals are not needed in enormous quantities, their absence can interrupt the manufacture of products because of broken supply chains or export stoppages. In such cases, the economic damage is likely to far exceed the material value of the imported metals.

Scarce and Expensive Raw Materials

The metals, whose weight in many everyday products is only a few milligrams, have to be mined by the ton. Take indium, for example, where the production of smartphones by the billions and the further development of photovoltaics have caused annual demand to rise from 50 tons in the 1980s to 1,000 tons today. The global reserves of a maximum of 15,000 tons are distributed among a few countries, such as China, Canada, and Peru, where it is extracted during the mining of zinc ores. This has its price. The price per kilogram for indium has risen by almost 80 percent in the past five years. For terbium, the increase was over 500 percent. In the medium term, therefore, there is much to suggest that the prices for these extremely precious spice metals could continue to rise.